Louise Berliawsky Nevelson

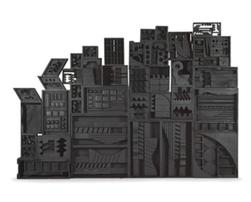

Creator of wood assemblages made from found objects and parts of furniture doused in black paint, Louise Nevelson became the darling of the New York art world, especially during the last three decades of her life when her success was assured. She cultivated an artistic image, was thin and draped clothes haphazardly on her figure, smoked small cigars, and wore exceedingly long, fake eyelashes.

Creator of wood assemblages made from found objects and parts of furniture doused in black paint, Louise Nevelson became the darling of the New York art world, especially during the last three decades of her life when her success was assured. She cultivated an artistic image, was thin and draped clothes haphazardly on her figure, smoked small cigars, and wore exceedingly long, fake eyelashes.

She was born Louise Berliawsky in Kiev, Russia, and at age five, moved with her family to Rockland, Maine where her father ran a lumber yard. In a town that was mostly Protestant, middle class, white people, she felt out of place as a Jew and an immigrant. In 1920, she moved to New York, studied at the Art Students League with Kenneth Hayes Miller, and married Charles Nevelson, whose “WASP” family she regarded as terribly stuffy. They had a son, and when he was nine years old, she went to Munich to study, separating from her husband and leaving her son for several years with her parents.

In Germany, she studied with Hans Hoffman until the Nazis drove him away, and then she studied in Paris before returning to America to raise her son and pursue her art career. From 1932 to 1933, she was in Mexico as an assistant to muralist Diego Rivera. In 1941, she had her first one-woman show, which was held at the Nierendorf Gallery in New York, but her break through did not come until 1957, when she began her box-like assemblages and received much critical acclaim.

In 1959, Louise Nevelson was one of “Sixteen Americans” in an important Museum of Modern Art exhibition. In the mid 1960s, she began welding found objects to welded steel, and directed a team of workers to make her black painted sculptures. For her, the color black symbolized harmony and continuity.

She also held several teaching positions including at the Educational Alliance in New York City; the Adult Education Program in Great Neck, New York; and at the New York School for the Deaf.

Nevelson lived to age eighty nine, and was much pleased that her son, Mike, also became a successful sculptor. In 1976, she wrote her autobiography, Dawns and Dusks, in which she credited her own determination for her success. In recognition of that success, the U.S. government in 2000 issued special Louise Nevelson commemorative stamps, with five varieties, each with a photo of one of her monochrome sculptures.

Sources include:

Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein, American Women Artists

Marika Herskovic, American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s