Art Styles, Colonies, History

California Art

California has long been a land that has inspired the imagination, from the time of the first Native Americans, through the tumultuous years of settlement, to the present. The story of art in California has many fascinating chapters: the Age of Exploration, the Spanish and Mexican periods, The Gold Rush, the Missions, the Railroad, the ‘Golden Age’ of Landscape Painting, the influence of European art, the evolution of two distinct centers of art in Southern and Northern California, the Great Depression, World War II and postwar to Modernism and beyond. Despite the state’s ‘late start’ on the national artistic scene, California painters have always been among the top ranks of American artists, and in the 1960s it might be argued they even took the lead for the country.

Spanish and Mexican Periods

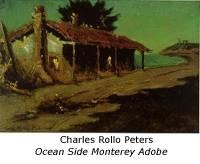

During the years of Spanish control (1769-1822) twenty-one missions were established in California, along with presidios and towns for settlers. The priests were not only good businessmen, they were also educated and often artistically sensitive. During the period of Spanish domination, art was primarily made for, or at, the various missions, and was most often the painted decoration of the interior of the churches. It was during this period that artists such as Jose Cardero (1768-1791) and Louis Choris (1795-1828) who accompanied expeditions, recorded views of the land, the presidios, and the population. Mexican revolutionaries broke Spain’s hold on California, and it became an empire in 1821. Rancho owners became the land’s aristocracy, but their tastes ran more to decorative arts, and pictorial art was kept alive mainly by artists coming from outside California with scientific expeditions, or by gentlemen travelers. Continuing interest in ‘mission art’ is reflected, however, in the work of late 19th-century resident painters including Henry Chapman Ford (1828-1894), Christian Jorgensen (1860-1935), William Lees Judson (1842-1928), Manuel Valencia (1856-1935), as well as into the 20th century with Charles Rollo Peters (1862-1928), see ‘nocturnes’, Florence Upson Young (1872-1974), Ellen Farr (1840-1907), and Minnie Tingle (1874-1926).

When war was declared between the United States and Mexico in 1846, some of the military engagements were recorded. Accompanying one U.S. battalion were artists John Mix Stanley (1814-1872) and William Hemsley Emory (1811-1887) who created pictures of people and places of that period. In 1847 California came under U.S. jurisdiction, and the first noted artist to arrive after the land had come under United States protection was Titian Ramsay Peale (1799-1885). Since most artists arrived by ship, their views are often confined to areas not far from the coast. For example, French engineer Jean-Jacques Vioget (1799-1855) painted early landscapes of the Klamath River and Mount Shasta; Alfred Thomas Agate (1812-1846) painted the upper Sacramento River; William Henry Meyers (1815-?) made drawings of San Diego and San Pedro; and James Madison Alden (1834-1922) traveled up and down the West Coast for almost a decade recording scenes from the Coast Survey ship on which he served.

The Gold Rush

The Gold Rush of 1849 attracted artists from the East Coast, some to prospect, others to create illustrations for magazines and books. Money was also earned by making panoramas, which were scenes painted on long rolls of canvas that could be viewed like today’s motion pictures. One of the most notable in this medium was Henry Miller (active 1856-1857). The most important result from such profit-from-art ideas was the development of a professional resident art community in San Francisco. Immigrant artists began to turn out oils and watercolors in a full range of subjects, displaying styles from the cities from which they had come. Particularly well-known artists of the Gold Rush era are German born Charles Christian Nahl (1818-1878), Alburtus Del Orient Browere (1814-1887), who made extended trips from his native New York, and Ernest Narjot (1826-1898) who came from France in search of gold in 1849. Narjot settled in San Francisco to paint, becoming one of the most accomplished artists in the city. An outstanding portraitist was William Smith Jewett (1812-1873), as was Nahl.

Statehood and the Railroads

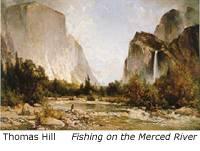

In 1850, California became the 31st state in the Union. By 1860, San Francisco was entering a 20-year economic boom with a developing upper class that patronized art. Portraits of prominent citizens were important in pictures commemorating historic occasions, such as the painting by Thomas Hill (1829-1908) commemorating the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, with Leland Stanford at its center. Aside from his portraiture, Hill is best known for his views of Yosemite Valley.

Several highly talented artists moved to the city and organizations such as the California Art Union, the Bohemian Club, the Graphic Club, and The San Francisco Art Association, formed to encourage the fine arts. When the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, artists could move more easily between the two coasts, and California’s magnificent landscapes were a great attraction for painters. The year 1874 marked the establishment of California’s first art school, The School of Design, in San Francisco.

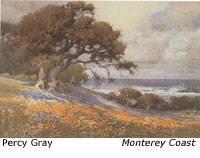

In the later 19th century, the city also attracted a number of ‘bohemians’, a term applied to persons who flouted bourgeois norms and enjoyed vagabond lifestyles. Bohemian artists found inspiration in San Francisco subjects, as well as the California wilderness. In 1873, two Frenchmen, Paul Frenzeny (1840-1902), who had been with the French cavalry in Mexico, and Jules Tavernier (1844-1889), who had fought in the Franco-Prussian war, were hired by Harper Brothers to sketch the American frontier for the magazine. Together they traveled on horseback from Denver to San Francisco, where both became active in the art community and became members of the Bohemian Club. The Bohemian Club, a men’s club founded in 1872, was originally a fellowship of journalists and other writers, but later expanded to include artists, musicians, and others interested in the fine arts. Tavernier and Jules Francois Pages (1833-1910) were founders of the Palette Club, a dissident group that in early 1884 rebelled against the dictates of the San Francisco Art Association. Pages’ studio was often a meeting place for San Francisco painters such as Julian Rix (1850-1903), Charles Dormon Robinson (1847-1933), Joseph Strong (1852-1899), and Samuel Marsden Brookes (1816-1892), as well as his good friend, Tavernier. Later, Tavernier founded the first art colony in the Monterey area, where he was joined by Frenzeny as well as Rix, Strong, Peters, and others.

The most nationally recognized landscapist to come to California at that time was Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) who was born in Germany, but was raised in Massachusetts. Bierstadt is especially noted for his paintings of Yosemite, as is English-born Thomas Hill. William Keith (1838-1911) painted Yosemite too, and while there met poet-naturalist John Muir, beginning a relationship that shaped his art. The subjects of painters such as Bierstadt, Hill, and Keith were often sublime panoramic views of the California wilderness, revealing the grandeur and drama of nature, in a style some term Romantic Realism. Other active landscapists of the period were Frederick Ferdinand Schafer (1839-1927), William Hahn (1829-1887), and Hermann Herzog (1832-1932), who rose to prominence in the 1870s.

With time, California artists moved away from grand panoramas and dramatic wilderness, and more towards pictures of lowland activities or intimate genre scenes. Albertus D.O. Browere (1814-1887) depicted fishermen. George Albert Frost (1843-1907) painted the mansion of W.C. Ralston. Marine paintings were created by Charles Nahl (1818-1878), Raymond Dabb Yelland (1848-1900), William A. Coulter (1849-1936), Joseph Lee (1827-1880), and Charles Dormon Robinson (1847-1933), thus reflecting the importance of the Pacific Ocean in the growth of the state. Some, such as Nahl, Browere, and Norton Bush (1834-1894) painted pictures of the tropics, having traveled the Isthmus of Panama en route to California. The fashion for the tropics sold well, both to romantics stimulated by their exotic themes, and to patrons as momentos of their own trips.

European Influences

During the 1870s and 1880s many of San Francisco’s artists went to Europe for advanced study at the popular centers of Dusseldorf and Munich. This European exposure changed their art, and those decades were the ‘glory days’ for the production of subjects such as history, still life, and genre, that were promoted in those German art centers. Some of the artists reflecting these influences include historical painters Toby Rosenthal (1848-1917) and Domenico Tojetti (1806-1892), still life painter Samuel Marsden Brookes (1816-1892), and Theodore Wores (1859-1939), who studied in Munich and once back in San Francisco often painted Chinatown subjects. California genre painters generally presented a carefree and bucolic way of life, with scenes of the industrial world and poverty rarely depicted.

Although Paris was a magnet for art students with means, few could pass the rigorous entrance exams at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, which included fluency in French language. The most popular alternative was the Academie Julian, an open-enrollment school, which attracted large numbers of foreigners from many nations, including Americans from California such as Guy Rose and Charles Rollo Peters. Other Californians who studied in Paris were Thomas Hill and Ferdinand Kaufmann. Due to restrictions regarding models, female students had their own studios at Julian’s. Among the California women artists who studied there were Matilda Lotz (1858-1923) who painted landscapes and portraits including Chinatown scenes; Elizabeth Strong (1855-1941) a painter of landscapes as well as animals; Evelyn McCormick (1862-1948) who painted townscapes, including Monterey; muralist and landscape painter Florence Lundborg (1871-1949); and portrait and genre painter Anna Klumpke (1856-1942).

Still-life painter Emil Carlsen (1853-1932) studied in France as well as Munich, and as a teacher at the San Francisco School of Design had strong impact. Edwin Deakin (1838-1923) created landscapes of ruins and historic architecture, as well as exceptional floral still-lifes, often of roses, which he cultivated at his Berkeley home.Alice Chittenden (1859-1944) was one of San Francisco’s most talented still-life painters at the end of the century. Interestingly, it was Chittenden, along withMaren Froelich (1868-1921), who in 1898 first broke the all-male monopoly at the Bohemian Club’s annual art exhibition. At the other end of the state, Frenchman and floral painter Paul De Longpre (1855-1911) lived in Los Angeles at the turn of the century on what is now Hollywood Boulevard, in a Moorish mansion where he flew both the French and American flags. There he planted thousands of roses and other flowers and is renowned for his mastery in painting them.

Centers of Art and New Styles

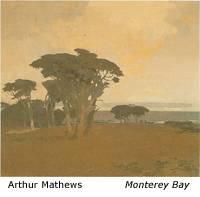

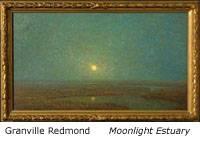

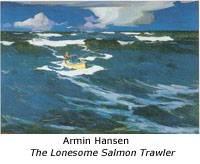

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, California art evolved through continuous innovation. San Francisco society struggled to define itself, and different styles of life coexisted in Northern California, varying between Victorian conservatism, to back-to-nature groups, as well as a lively bohemian community. The ‘California Decorative Style’ developed in the Bay Area at this time, as seen in lyrical tonalist compositions by Arthur Mathews (1860-1945) and Francis McComas (1875-1938). Tonalism, unlike the Impressionist free use of color, conveyed quiet mood and atmospheric effects, as is seen also in the work of Xavier Martinez (1869-1943), Thomas McGlynn (1878-1966), Henry Percy Gray (1869-1952), Granville Redmond (1871-1935), Giuseppe Cadenasso, (1858-1918), and Gottardo Piazzoni (1872-1945). Prior to the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, many important artists of the next generation were students of Mathews at the Mark Hopkins Institute of Art, including Martinez, McComas, Piazzoni, Armin Hansen (1886-1957), Clarence Hinkle (1880-1960), Ralph Stackpole (1885-1973), and Maynard Dixon (1875-1946).

Three expositions, which also featured European works, were the California Midwinter International Exposition of 1894 in San Francisco (a portion of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition of Chicago), the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 held in San Francisco, and then in San Diego in 1915-1916. These events exposed the public to examples of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Expressionism. Bruce Nelson (1888-1952) was the silver medalist at the 1915 PPIE.

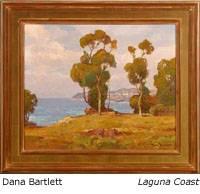

Beyond San Francisco, art centers emerged along the coast in places such as Carmel-Monterey, Santa Barbara-San Luis Obispo, Los Angeles, Laguna Beach, and San Diego.

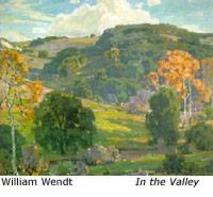

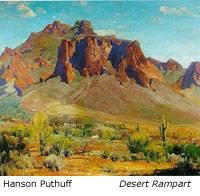

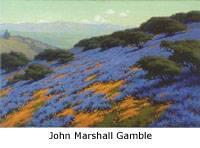

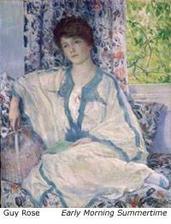

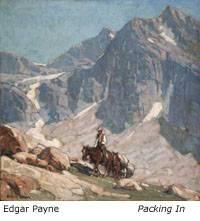

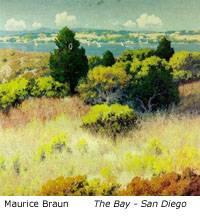

Influenced by Impressionism, plein-air painting (painting outdoors) became the dominant style in the first decades of the 20th century, as represented in canvases by Maurice Braun, (1877-1941), Granville Redmond (1871-1935), William Wendt (1865-1946), and Hanson Puthuff (1875-1972). Guy Rose (1867-1925) is generally considered to be the state’s most accomplished Impressionist. In the work of these artists a new style emerged, a ‘California style’ of Impressionism with innovations that set it apart from that in Paris or New York. Some of this uniqueness may be attributed to ‘California light’ and the way it impacted artists. It may also be due to that fact that many California Impressionist painters, while working on the west coast, also studied at academies in other areas of the United States and abroad; they saw exhibitions, traveled, knew vast and open spaces and brought this experience to California art. Many of them were also teachers.

Some of the California women artists who advocated this shift in taste from the somber tones of the barbizon or decorative styles towards the brighter more vigorous themes of Impressionism were Donna Schuster (1883-1953), Henrietta Shore (1880-1963), and Euphemia Charlton Fortune (1885-1969), all of whom exhibited at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 in San Francisco.

Early California women Impressionists were Lucy Bacon (1857-1932), Evelyn McCormick (1862-1948) and Mary Brady (1867-1940), the latter two both part of the colony at Giverny. Although she is less known than some other artists, Bacon’s story is an intriguing. She had attended art school at the Art Students’ League and the National Academy of Design in New York before leaving for France in 1892. Apparently possessed of no small degree of determination and direction, she contacted Mary Cassatt for advice, and wound up studying with Camille Pissaro, making her perhaps the only artist associated with California Impressionism to have studied with a French Impressionist. Bacon received a good deal of support in her adventures from her brother, Albert Vickery, a merchant in San Jose, California. Bacon was related by marriage to Robert K. Vickery of Vickery, Atkins and Torrey, an important gallery in San Francisco in the 1890s.

Nocturnes

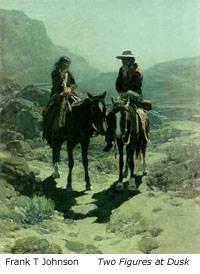

At the turn of the century, night scenes, or nocturnes, were popular with romantic-minded Victorians who were entranced by the mystery created when pale light, like that from the moon, obscured details. Among those who painted California nocturnes are:Sydney Laurence (1865-1940), Charles Rollo Peters (1862-1928), Will Sparks (1862-1937),Charles Walter Stetson (1858-1911), Frank Tenney Johnson (1874-1939), and Granville Redmond (1871-1935). Although he is best known for his paintings of Alaska, Sydney Laurence was Los Angeles based. He emphasized the enigma of California mission ruins in his nocturne work ‘Evening Star, Mission Capistrano’, where he dissolves the arcade of the mission in a fog, and adds a spiritual element via a single shining star, a feature frequently seen in his work. Pasadena painter Charles W. Stetson was taken with that region’s beautiful moonlight, as in his work ‘An Easter Offering’, where moonlight bathes one of the commercial fields of white calla lilies that once grew in the area. Frank TenneyJohnson, who settled in Alhambra, California, around 1930, specialized not in the inky versions of nocturnes produced by Tonalists such as Peters, but rather in blue-toned views of cowboys and cattle under a full moon. His subjects were quiet, such as pack trains wending their ways, night herders regarding their bedded-down cattle, or lone cowboys in philosophical contemplation.

Granville Redmond, who lived both in Northern and Southern California, painted not only his famous fields of poppies, but also enchanting coastal nocturnes. Tonalist painter Charles Rollo Peters, who was of the same generation and palette as Arthur Mathews, studied in Paris, where James Whistler had a studio. It is said that Whistler stated Peters was “the only artist other than himself who could paint nocturnes”. (California Painting, 450 Years, by Nancy Moure). After extensive touring throughout Europe, Peters returned to California, where he eventually settled on a large estate in Monterey. There the artist specialized in moonlit nocturnes featuring romantic depictions of Monterey’s old Spanish missions and adobes painted in a deep tonal palette, often with his trademark of soft light showing through a window. These works earned for Peters the nicknames “The Poet of the Night” and “The Prince of Darkness”. Will Sparks also painted many pictures of crumbling humble adobes set in a moonlit landscape, which has caused his name to be linked with that of Charles Rollo Peters. Sparks’ paintings reveal his particular fascination with twilight scenes that combine the effects of both natural and artificial sources of light.

The Old Lyme Colony was named for painters in Old Lyme, Connecticut, a village that hosted the first major art colony in America that encouraged Impressionism. Old Lyme was accessible to its New York City-based painters by excellent rail service and was located at the confluence of the Connecticut River and Long Island Sound. The period of its greatest activity was 1900 to 1915.

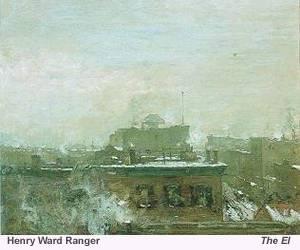

Joseph Boston was apparently the first artist to have visited and painted in Old Lyme, in 1894, conducting the Westhampton Summer School of Art there, but the town was first ‘discovered’ by Clark G. Voorhees on a bicycling trip in 1893. Henry Ward Ranger, considered by many to be the most acclaimed artist of the region, was already in the vicinity, but it was Voorhees’s recommendation that sent him to Old Lyme in 1899. There he boarded in the slightly run-down mansion of Miss Florence Griswold, whose home rapidly became a mecca for successive waves of summer painters. Ranger took a group of his artist friends to Miss Florence’s in 1900, and transformed Old Lyme into an ‘American Barbizon’, where he became one of the acknowledged leaders of Tonalism at the turn of the century. Ranger sought a bucolic place that was scenic, quiet, and remote and that reminded him of the village of Barbizon, France, where as a young man, he had taken up painting bucolic scenes in a Tonalist style. He sought a bucolic place that was scenic, quiet, and remote and that reminded him of the village of Barbizon, France, where as a young man, he had taken up painting bucolic scenes in a Tonalist style.

Connecticut Old Lyme Colony

n 1903, the arrival at Old Lyme of well-known American impressionist Childe Hassam caused Ranger’s tonalist influence to dwindle and the place to take hold as a bastion of Impressionism. The Florence Griswold House, now a museum devoted to the work of its former occupants, was the gathering place for these artists, and, as stated above, living at Griswold House became the first step to acceptance into the Colony AskART.com personnel, having referred to books and Old Lyme art historians, includes those artists who were considered by each other as members of the Colony. All landscape painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they were an unofficial but well-defined group whose exclusivity was determined by who was allowed by Florence Griswold, counseled by other artists, to stay at her boarding house.

Of this group, most had their primary residences on the East Coast in New York, Massachusetts, or Connecticut. Several became Midwesterners including Louis Dessar from Indiana,Alonzo Kimball and Louis Betts from Illinois, George Newell and Frederic Ramsdell from Michigan. Maurice Braun was the only Californian, andArthur Heming was Canadian.

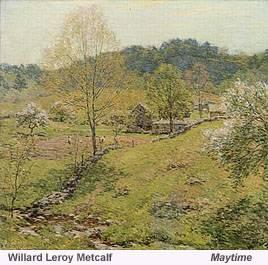

Artists with considerable book mentions, as well as museum representations, areChilde Hassam, John Twachtman, J Alden Weir, Theodore Robinson,Willard Metcalf, Gifford Beal, andEmil Carlsen. That same group plusMaurice Braun and Guy Carleton Wiggins experience high prices at auction.

Credit for parts of the above information is given to William Gerdts, author of Art Across America, as well as to American Art Review, 6/1997. FLORENCE GRISWOLD MUSEUM by Jeffrey Andersen, and American Art Review, 8/2002, EARLY YEARS OF THE LYME ART COLONY by Pamela Bond

Illustration Art: America’s Visual History

In the United States, tracking illustration art originating with drawing and painting involves thousands of artists through time-lines touching every event in American history that impacted daily lives. From topics shared by the entire nation such as the Civil War to private moments of a soldier ‘oogling’ a pin-up taped to his locker, the totality of this country’s illustration is America’s story in pictures.

Logically, one might ask: What is Illustration? Ralph Mayer in his book, A Dictionary of Art Terms and Techniques, defines it as a “picture especially executed to accompany a printed text, such as a book or an advertisement, in order to reinforce the meaning or enhance the effect of the text.” (191) Pruett A Carter, (1891-1955), a women’s magazine illustrator, said: an “illustrator may be likened to the director of a motion picture. . . He must live the part of each actor. He must do the scenery, design the costumes, and handle the lighting effects.” (Taraba)

Beginnings

Beginnings are tied to the development of printing processes such as lithography that facilitated the widespread copying of images. New Yorker Nathaniel Currier (1813-1888) and his lower Manhattan lithography firm of Currier & Ives pioneered mass production, and became the most famous and longest operating printing company in America. The company opened in 1834 and closed in 1907. National attention came quickly because of widely circulated prints in 1834 of a catastrophic fire that year in New York City. Much enhanced by imagination, these copies were hawked on the streets, just like newspapers, by hired persons shouting, “extras, extras”. Currier & Ives produced more than 1,000,000 lithographic prints of over 7,000 picture subjects including colonial America, the Civil and Spanish-American Wars, and sentimental and social-realist genre scenes.

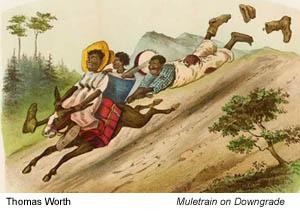

Starting their art careers making images for lithographic copies in the Currier and Ives design department were persons whose names are remembered much more as 19th-century fine-art painters than illustrators. But for these persons, illustration meant ‘bread and butter’. Names include Eastman Johnson (1824-1906), Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait (1819-1905), Louis Maurer (1832-1932), James Buttersworth (1817-1894), and William Aiken Walker (1838-1921). One of the most popular Currier & Ives illustrators was Thomas Worth (1834-1917), who was appreciated for his Darktown series combining racism and humor and for his highly popular depictions of hunting, fishing and horse racing.

Behind the scenes were teams of women working at tables, each repetitively applying a single color under the direction of a supervisor. The female artist most associated with the business name of Currier and Ives was Fanny Palmer (1812-1876). Her specialty was painting backgrounds as well as planning color schemes and making critical improvements to the lithographic crayon used by the firm. In those days, it was unusual for women to be named publicly for their roles in illustration, but she, a genteel but poor woman married to an alcoholic, was much respected by her peers. Illustration scholars prevent her name from being forgotten.

George Henry Durrie (1820-1863), dubbed “The Snowman” for his sentimental genre and landscape winter scenes, expressed the romantic, idyllic pre-Civil War vision that many people of comfortable means had of American life: happy figures ice skating and sledding, flirting couples in playful games of tag, and New England farms encased by deep, pure snow with homes whose sparkling lit windows gave the message that all was beautiful outside and cozy and loving inside. For many, it was a vision of the perfect world, but unfortunately for most, it was more imagined than real.

During the Civil War and post-war period, the public’s interest in national news, especially the sensational, was intense, and the only sources of that news with visual supplements were magazines and newspapers. Leading publications among educated people were Leslie’s Illustrated News, Harper’s, Atlantic, The Century Magazine, Scribner’s and McClure’s Magazine. During the Civil War, publishers of Harper’s Weekly printed and sold over a million copies each month, and seeing their success, other publishers added artists to their staff. Several aspects of the ‘start-to-finish’ process of that period could be highly frustrating to illustrators, especially the lag time from the illustrator’s hand to publication. In her book, The Red Rose Girls, Alice Carter describes a common scenario: “Drawings were tucked in leather bags and rushed by mounted messengers from the battlefield to the engravers, where craftsmen quickly traced the artists’ designs on the end of blocks of fine-grained boxwood. Often when the sketches arrived at the engravers, they were cut into four pieces—a process that ruined the original artwork but allowed four different craftsmen to incise the design onto separate blocks . . .” (p. 24) The blocks were then bound together and sent to the master engraver who smoothed the juncture lines. It was very time consuming because the engraving of each block could take about twelve hours.

For illustrators traveling on assignments, the time gap could be weeks or months because of inefficient delivery methods back to the publishers and their block copiers. And it was not unusual for the sketch artist or illustrator to be frustrated with the engraver, who in making the copy sometimes became “creative”. This meant that final copies often did not resemble originals, and because of these intervening hands, illustrations frequently did not credit list the illustrator’s name.

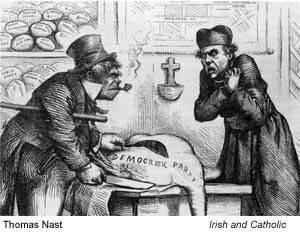

An exam ple of ‘intervening hands’ isThomas Nast (1840-1902). One of his assignments during the Civil War was translating the hurried drawings of reporters into finished drawings for the engravers. However, this endeavor made him unpopular with his peers because he sometimes applied his own signature to the work. Nast also did much original war illustration. Working for Harper’s Weekly, he was a political cartoonist and caricaturist whom Abraham Lincoln regarded as one of “the most influential recruiters for the Northern cause.” (Reed 21) Nast also made several ongoing contributions to images that became ensconced in American culture. Illustrating Clement Moore’s The Night Before Christmas, he invented the ‘jolly, benevolent fat man’ image of Santa Claus. In American politics, the cartoon drawings of the Republican elephant and Democrat donkey came from Nast’s cartooning pen. Although most Civil War illustrators are not documented on their original works, certain names do get retr ospective credit. Winslow Homer’s(1836-1910) first income as an artist came from his work for Harper’s from 1859 to 1883. Traveling with the Army of the Potomac from October 1861 to May 1862, he filled his sketchbook with studies of uniforms, weapons, individual soldiers and battle scenes. He did first-hand sketching at the Battle of Yorktown in 1962. And Theodore Davis (1840-1894) was described as “covering more areas of the fighting than any other artist, including a junket in the South in 1861.” (Reed 16) The name of Philadelphian Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1822-1888) is easily associated with Civil War illustration because, unlike most of his peers, he stayed at his work table producing signed works that were “precise monochromatic paintings of important battles and engagements” (Carter, Red Rose Girls, 25). Thomas S. Sinclair (1805-1881), whose Philadelphia firm specialized in stone lithography, was the master engraver who converted Darley’s works into steel engravings.

Minolta DSC

Into the West

After the Civil War, illustrators, like so many other Americans headed West to explore a part of the country mostly untouched by the war and open to future expansion and adventure. Many of them were on assignments from publishers of the above-mentioned periodicals. An especially notable post-Civil War, western-expansion magazine-story assignment is linked to the 1898 venture of Ernest Blumenschein (1874-1960) andJoseph Henry Sharp (1859-1953). They were sent by S.S. McClure of McClure’s Magazine to the Southwest to sketch landscape and inhabitants, especially Native Americans. They traveled from New York to Arizona and New Mexico, and inadvertently stopped near Taos because of a broken wagon wheel. Becoming aware of the dramatic landscape, its unusual lighting, and exotic subject matter of Pueblo Indians, Sharp and Blumenschein exchanged illustration for plein-air easel painting. Other artists followed, and became part of The Taos Art Colony that lasted until the beginning of World War II.

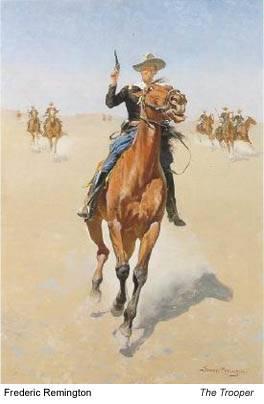

Likely the most famous names ‘ever’ linked to western illustration are Frederic Remington (1861-1909) and Charles Russell (1864-1926), although Remington did much more illustration than Russell, who mostly painted for himself. About the same age, both were basically self-taught artists who spent time in their early lives adventuring and recording the West. Russell, who grew up in St. Louis, was most interested in Native American subjects, while Remington depicted the white man encountering the West, especially ‘rough and tough, shoot-em-up’ cowboys and U.S. Cavalry figures.

Post-War Developments

Following World War II, the American economy in lockstep with technology and educational opportunity took off. For illustrators, this expansive period meant an exploding number of directions: ad designs for printed media and television, business reports, paperback novels and non-fiction as well as periodicals.

However, these changes led to dropping out of illustration by some highly talented artists because a market was developing for ‘art for art’s sake’. With money in their pockets, they could paint on their own schedules to audiences of their choosing. Because of extensive background in realist styles, narrative approaches, and in American history, many of these transition illustrators became western-theme artists in the tradition of Frederic Remington and Charles Russell.

Cowboy and horse painter Oleg Stavrowsky(1927-) credited his career of several decades in illustration as teaching him the discipline and work ethic necessary for artistic success, but rebelled against “art directors with far less artistic skill than his own.” He described his decision to change course to a time when he was standing in a gallery at the National Cowboy Hall of Fame: “Surrounded by all that magnificent art in Oklahoma City, I suddenly realized that I could be in complete control of what I was painting—the style, the content—” (Sinclair 78)

Moving to Wyoming in 1968 to become a western artist, James Bama (1926-) left New York City and a career with ‘slick magazines’ and pulp novels (Doc Savage). He built his own studio, and by 1971 was turning down all illustration jobs. In 1975, Tom Lovell moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, leaving behind a forty-year illustration career. He turned to historical western subjects in classical realist style, and was such a perfectionist that his output was limited to about twelve paintings a year.

Nicholas Eggenhofer, who had a brisk market for his dry-brush paintings in the Western pulps, later had much success with gallery paintings depicting “scrupulously accurate Western towns, wagons, coaches, cattle drives and buffalo hunts.” (Scottsdale Art Auction, 17) Kenneth Riley (1919-), magazine and historical fiction illustrator in New York, settled in Tucson, Arizona, and earned a distinguished recognition for western paintings, especially Indian figures in a style combining Luminism, Realism and Impressionism. Other eastern illustrators who had successful ‘second careers’ as western painters include John Clymer, Frank Hoffman (1888-1958), Frank McCarthy(1924-2002), Robert L ougheed (1910-1981), and Howard Terpning (1927-).

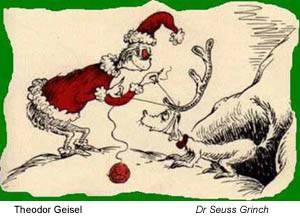

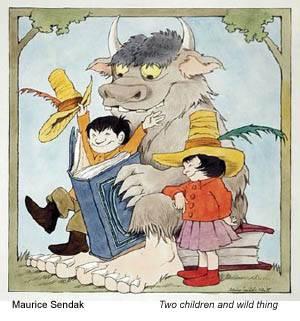

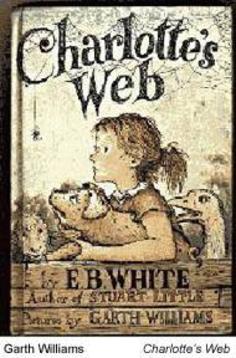

Children’s literature became popular when parents in a relatively settled post-war era could focus on more enrichment for their young families. And, of course, young readers loved eye-catching, entertaining illustrations. Theodor Geisel/Dr. Seuss(1904-1991), a professional cartoonist and the creator of Gerald McBoing-Boing, began writing his Dr. Seuss books in 1937, just before the war, and continued into the 1980s, completing forty-five publications. The series became so popular that he is credited with helping many children to learn to read. Maurice Sendak (1928-) began writing and illustrating his fantasy-creature children’s books that continue to push the boundaries of defining children’s literature. For his book, Where the Wild Things Are, he has won awards including the Caldecott Medal in 1964, and the International Hans Christian Anderson Award in 1970, the first American illustrator to receive that recognition. Hardie Gramatky (1907-1979) did magazine illustration assignments about tug boots in the New York harbor. The subject inspired him to create a series of Little Toot books, and the first one, Little Toot, (1967) is rated by the Library of Congress as one of the “gre at children’s books of all time.” (Reed 276)Garth Williams (1912-1996) illustrated some of the most famous children’s books of the late 20th century: Stuart Little andCharlotte’s Web by E.B. White, and Little House on the Prairie and others in that series by Laura Ingalls Wilder.

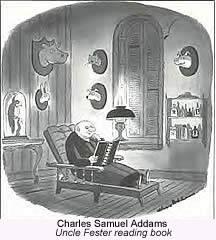

Humor and cartooning in illustration was more than welcome among the post-war public. Al Hirschfeld (1903-2003), caricaturist and cartoonist, had a long career with The New York Times, depicting entertainment notables. Walt Disney(1901-1966) and his Disney Enterprises in California employed many illustrators for movies and set designs in the 1950s at the newly-built Disneyland at Anaheim. Mary Blair (1911-1978), whose background was children’s book and magazine cover illustration, created tile murals and designed several rides for Disneyland including the overall design and individual characters for the famous ride, “It’s a Small World”, which was introduced at the 1964 Wor lds Fair. She also did a giant mural for the Contemporary Hotel at Disneyworld in Orlando, Florida. Carl Barks (1901-2000) illustrated the first Donald Duck comic books stories beginning 1942, having gone to work for the Walt Disney Company for $20.00 a week in 1935. Barks gave Donald Duck the personality for which he is known, saying that he strove to make him a sympathetic character and not just “a quarrelsome little guy.” (Goulart, 17).

Movie poster illustrator Reynold Brown(1917-1991) worked for Disney as well as Universal Studios, MGM, and American International Pictures. For Universal, he organized over 250 promotional campaigns with his poster designs including Cat on a Hot Tin Roof with Elizabeth Taylor and The Alamo with John Wayne and Richard Widmark. Like so many he leaned on Hollywood when he was financially needy, but once he was financially secure, he said ‘goodbye’ to assigned illustration work, and transitioned into self-directed western painting. Bob Peak (1927-1992) first did magazine illustrations and then poster painting for more than 100 motion pictures including My Fair Lady and Star Trek.

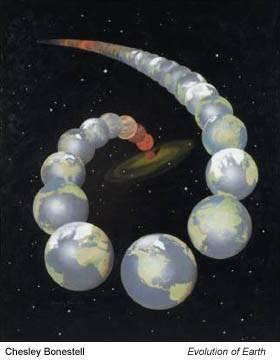

Top names associated with space-age illustration are Chesley Bonestell (1888-1986), Robert McCall (1919-) and Paul Calle (1928-). Bonestell did a series on space travel for Collier’s magazine and now has work in the Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville Alabama. McCall of Arizona was a World War II bombardier instructor and documentary artist for the U.S. Air Force. He has completed numerous commissions including huge murals for the Space Museum in Washington DC and for Disney EPCOT center in Orlando, Florida. Calle, who is from Connecticut, has a background in magazine illustration including work for The Saturday Evening Post, McCalls, and National Geographic. Skillful with detailed pencil drawings as well as painting, he became the official artist in 1962 of the Fine Art Program of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. This commitment has involved him in many NASA projects including the U.S. Postal Service design in 1969 of the “First Man on the Moon” stamp, which had a run of 150 billion.

In the second half of the 20th century, many of the traditional family magazines ‘bit the dust’ including Collier’s in 1956 and, as mentioned earlier, the Saturday Evening Postin 1969. Sports Illustrated remained strong, switching from photography to on-site finished painting with assignments such as Al Parker going to Monte Carlo for the Grand Prix auto race, and Stanley Meltzoff(1917-) donning underwater attire for a lengthy series of deep-water diving pictures. Responding to increasing public interest in foreign cultures and modern inventions, he also did work for National Geographic andScientific American. This ‘instant’, at-the-scene type of illustration allows the image-maker much more flexibility, creativity and interpretative power than drawing board or easel methods. A negative for editors or the assignors is loss of control over the slant of the story.

Life magazine’s heydey was during World War II when its on-site photographers and illustrators told the story of the war as it unfolded. However, for coverage of the Vietnam War and Civil Rights, the editors relied mostly on photos rather than artist renderings, and this replacing of illustrators by photographers seemed to be the trend in printed news media. Countering this trend was Tracy Sugarman (1921-) of Connecticut, who did such a remarkable job of on-the-spot drawings in Mississippi during the Civil Rights marches in the 1960s, that CBS featured them in a documentary, and editors of The Saturday Evening Post and The New York Times had them reproduced for their publications.

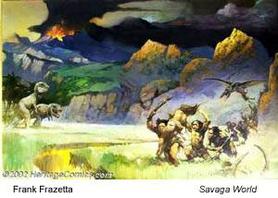

Mad Magazine, Playboy, Time, Newsweek, R eader’s Digest and Sports Illustrated were some of the successful magazines that made it through the 20th Century. And Frank Frazetta, (1928-) did work for all of them, having become established with pulp fiction and comic book illustration. He attracted a cult following for his fantasy works that combined sex, violence, exotic settings and high melodrama. Patrick Nagel (1945-1984) living only 38 years, devoted most of his early career to Playboy for whom he created his signature line paintings and drawings with flat color and sensual poses that became known as “Nagel Girls”.

For illustrators of the 50s and 60s and moving forward, creating covers to meet the national fad for paperback books saved them financially. According to Walt Reed in his book Illustrator in America, many of these commissioned “cover paintings were fine enough to compete with the art of Thomas Dewing and Renoir or other paintings . . .Other covers could be shamelessly exploitive of sex, whether representative of the contents or not” (335). Looking back on this period, Ed Schilders, a reviewer, wrote of these paperbacks that they were “brooding, colorful, realistic, and often vaguely pornographic” and went through periods of being dismissed as works of art and now have become sought after by collectors.

The genesis of these paperbacks was in reprints of popular novels before World War II, and when paper rationing was lifted after the War, their market soared. Illustrators taking advantage of this market includedJames Avati (1912-2005), a former women’s magazine illustrator who turned to paperbacks and is credited as a pioneer in setting the format; Frank Frazetta, who had paperback publishers vying for his services; and James Bama who transitioned from theSaturday Evening Post to paperback covers. In a later period, Pino, whose full name isGuiseppe D’angelico Pino (1939-), began his book cover career with Zebra Books in 1980, and for the next thirteen years, become a leading illustrator of romance novels for publishers including Bantom, Simon and Schuster, Harlequin, Penquin USA and Dell. His work is described as having powerful sensuality, bringing the medium of book-cover illustration to new heights.

From the 1970s forward to the end of the 20th and into the 21st centuries, illustration art has exploded into many directions including computer technology that leads into graphic arts and methods divorced from traditional illustration art methods of painting and drawing—an intriguing subject outside the boundaries of this essay. However, questions very pertinent to this discussion are what is the present status of illustration art in American culture, and what does the future seem to hold?

Looking Ahead

The interest of collectors and strength of the marketplace indicate a strong resurgence of interest in American illustrators and their creative output. Rising from the low-rung status of being perceived as ‘not-really-art’ in the mid 20th century, illustration has a rising star; rejuvenation is in the air.

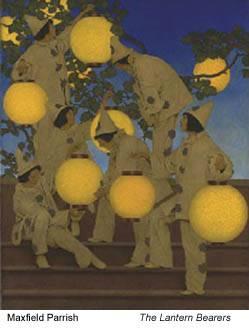

Substantiating this assertion that illustration art is ‘coming back’ in the fine-art market are record-breaking prices in 2006, which placed Norman Rockwell and Maxfield Parrish among the top 100 high-dollar American artists at auction within the last 20 years. On 5/24/2006, Homecoming Marine by Norman Rockwell sold at Sotheby’s New York for $9,200,000. This price realized was an increase of $4,240,500. from his previous highest record obtained in 2002. On May 25, 2006, Daybreak by Maxfield Parrish sold by Christie’s New York for $7,632,000., a price jump for Parrish of over 3 million dollars from his previous record.

Much credit for this renaissance is owed to Roger and Walt Reed of Illustration House in New York City and to Walt Reed’s books detailing the history of American illustration as visual art. His last book, The Illustrator in America 1860-2000, updates earlier two earlier versions (1966 and 1984) and edges the subject into the 21st century, which he describes as “an exciting new period”. (7)

Sharing the optimism of Walt Reed, Jim Halperin, Co-Chairman of Heritage Auction Galleries in Dallas, Texas writes:

“Illustration today is what history painting was in classical times: the noblest of genres. Instructive and inventive, this is the art of the public at large, particularly in America. Thomas Moran (1837-1926), whose romantic Western landscapes inspired the creation of our National Parks system, as well as Winslow Homer, Frederic Remington, and Maxfield Parrishall made their reputations through magazine illustration and then later as popular print makers. Their work hung in thousands of parlors across the nation. And during the 1920s when Parrish was the single most popular American artist, it is estimated that his prints hung in 25% of all American homes.

Today, formerly pigeon-holed illustrators such as Norman Rockwell, N.C. Wyeth, and J.C. Leyendecker have finally transcended the illustrator label, invariably offered at “Important American Paintings” sales and the finest private galleries. These and other great illustrators have created a beauty that resides in narration as well as in design. The importance and growing appreciation of the art of illustration should not be underestimated. The market for these paintings continues to grow both in valuation and in the number of recognized artists – trends that we expect will only continue or accelerate.”

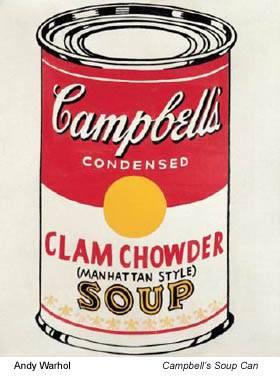

The rescue of illustration from a symbolic shelf labeled “not fine art” occurred in the 1960s with Pop Art, a movement among painters and sculptors blatantly showcasing realistic common objects. Among Pop Artists are Jasper Johns, Jeff Koons and Roy Lichtenstein, but the leader was illustrator Andy Warhol (1928-1987) whose roughshod treatment over those turning up their noses at illustration-related images seems to have had a permanent effect. Warhol’s gallery-exhibited paintings and silk-screens of popular objects, such as frequently advertised images such as Campbell Soup Cans, Brillo Pads and Coca Cola bottles, shook up the mid-20th century’s American art world, especially those critics and collectors wedded to abstraction. Art historian Peter Falk in Who Was Who in American Art described Andy Warhol as the first artist “to elevate both common and famous photographic images from popular culture to fine-art status.” (3465). Apparently that counter influence is ongoing. In May, 1999, editors of ARTnews magazine named Warhol one of the twenty-five most influential artists ever.”

Although much controversy can be stirred by discussions of illustration art, meaning that which is created by third-party assignments and contracts for payment, one conclusion seems obvious. Without America’s illustrators—that long succession of engravers, sketch artists, drawing masters and easel painters—the country would be devoid of visual components of its narrative history. Most of us would acknowledge that contribution as a critical part of the nation’s artistic heritage.

Written by Lonnie Pierson Dunbier, May 2006

SOURCES:

Books: Matthew Baigell, Dictionary of American Art; Alice Carter, Cecilia Beaux, A Modern Painter in the Gilded Age and The Red Rose Girls, an Uncommon Story of Art and Love; Alma Gilbert-Parrish, Maxfield Parrish, Master of Make Believe; Tony Goodstone, Editor, The Pulps; Peter Haining,The Classic Era of American Pulp Magazines;Robert Lesser, Pulp Art; Ralph Mayer, A Dictionary of Art Terms and Techniques; Walt Reed, The Illustrator in America, 1860-2000;Charlotte Rubinstein, American Women Artists; Peggy and Harold Samuels, The Illustrated Biographical Dictionary of Artists of the American West; Michael David Zellman, 300 Years of American Art

Periodicals: American Arts Quarterly, Editor, “Exhibitions-American Illustration”, Winter 2006; Marjorie Goldsmith, “Illustrious Achievements”, Art & Antiques, April 2006, pp. 60-64; Heather Haskell and Liz Sommer, “Currier & Ives: An American Panorama”, American Art Review, November-December 2005; Paul Sinclair, “Oleg Stavrowsky: A Fierce Individualist”, Wildlife Art, May/June 2006, pp. 76-79

Looking Ahead

In the 1920s, 30s and 40s escapist literature called Pulp Fiction, was a major player in the illu stration/publication market. An immersion in fantasy, it was a quick-read—a much-needed antidote to world wars and food and money shortages. The widespread popularity of ‘low-brow’ Pulp Fiction mixed with other commercial aspects of illustration stirred accusations, especially from 1950s Abstract Expressionist painters and their promoters, that illustrators were not ‘real’ artists. The argument was that paintings and drawings by illustrators were not linked to personal expression and creativity, the traditional spheres of fine art, but were merely assignments completed for outsiders in exchange for money. In other words, anybody who did artwork under pressure of editor deadlines and subject assignment was in violation of the aesthetics that defined a ‘real’ artist.

Excluded and temporarily sidetracked in the public’s appreciation for several succeeding decades were not only pulp illustrators,but other highly talented and respected artists such as Norman Rockwell, Maxfield Parrish and N.C. Wyeth.

Well-known pulp monthlies included Argosy, Blue Book, Popular, Excitement, Amazing Stories, Black Mask Top-Notch. Heroes were The Shadow, The Spider, Doc Savage, The Phantom, Tarzan and Operator #5. Dr. Kildare, Zane Grey and his many western adventure novels, and Edgar Rice Burroughs Tarzan and the Apes. Science Fiction, Adventure, Horror Stories, Romance, Westerns, Religious Drama and Detective Plots were popular subjects.

‘Pulps’ were mass-produced by a formula that insured low-cost volume—cheap paper and dry-brush interior illustrations to avoid the cost of half-tone engraving. The primary cost and the key to selling the issues was the cover art, “often with flesh-creeping, brain–haunting pictures of men in pain and women in terror of what was about to happen to them. . . those with the most bright, excitement, and senses-pounding colors per square inch won.” (Lesser 6) Dry-brush drawings earned the creator ten to twenty-five dollars for a double-spread and seventy-five to one hundred fifty dollars for a full cover in oil. Pulp illustrators during the Depression earned from fifty to three-hundred dollars per cover, which “was a starting place for young artists on the way up and a haven for veteran illustrators on their way down.” (Lesser, 51)

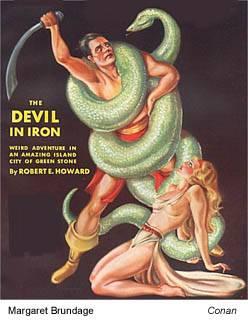

Among the top Pulp illustrators were Rudolph Belarski (1900-1983), who depicted aviation and science fiction subjects and Walter Baumhofer (1904-1987) described as the “King of Pulps” for being so prolific and creating more than 1500 pieces including western novels about about “Doc Savage”, and pieces for Liberty magazine. Nick Eggenhofer (1897-1985), traveling extensively in the West, did more than 30,000 illustrations, and was at the forefront of those pulp illustrators portraying the wagon-train, frontier settlement era. Margaret Brundage (1900-1976) of Chicago illustrated for Pulps in the 1930s, and became known for her, “Brundage beauties”, ladies in distress. With her story illustration The Slithering Shadow, he was the first of the pulp artists to depict torture, something she introduced in a whipping scene.

Science fiction and fantasy pulp artists tended to be regarded as being in a world of their own and were considered, not only by artists exploring abstract art, but by their illustration peers as somewhat peculiar. Although fantasy subjects had fiercely loyal fans, its publishers had the lowest circulation and the lowest pay scale for its artists. James Allen St. John (1872-1957), chosen personally by Edgar Rice Burroughs to illustrate his Tarzan stories, was one of the leading fantasy artists.

Other distinguished names among pulp illustrators are Norman Saunders (1906-1988, Gerald Delano (1890-1972), Robert George Harris (1911-), Herbert Morton Stoops, twin brothers George(1895-1974) and Jerome Rozen (1895-1987), Richard Lillis (1899-1995), Ernest Chiriacka (1920-), John Clymer (1907-1989), Harold Winfield Scott (1898-1977), A. Leslie Ross (1910-1989) andJohn Gould (1906-1996), who estimated he did about 12,000 pulp illustrations before turning to “the slicks” such as Redbook, Colliers and The Country Gentelmen.

By the end of the 1940s, the demand for pulp fiction illustration subsided due to photography replacing much of the visual material that had been hand-painted, and also due to lessening demand for sensationalism from a country whose real circumstances were getting better and whose populace could find happy diversion in reality.

Sacrificed with the ebbing of pulp fiction was much of the original cover art because these drawings and paintings were regarded as being without value once they had been used. Eventually a majority of the originals ended up in New York garbage trucks, having been discarded in midtown Manhattan and Lexington Avenue, which was the center of pulp printing and publishing. According to illustration art scholar Roger Reed, “Of an estimated fifty-thousand paintings made for all pulps, only about 1 percent has been recorded to survive today.” (Lesser 8)

Because of the need for money, many illustrators were willing to become targets of accusations of selling out aesthetically. And a positive was that editors of the “slicks” such as The Saturday Evening Post and McCalls regarded the pulps as a training ground for illustrators of their more ‘high-minded’ publications. In this ‘more refined’ group were Amos Sewell (1901-1983), Robert G. Harris, and John Falter (1910-1982). However, some of the ‘slicks’ were folding. In the 1930s, with ravages of the Depression and audiences wanting a less-lofty form of entertainment, Vanity Fair, Judge, Smart Set and the original Life magazine ceased publication. But other periodicals survived such as Fortune, a men’s fashion magazine launched in 1933. They added fiction, travel and sports and a full page by George Petty (1894-1975) of his ‘Petty Girls’, meaning young females with skimpy attire. The New Yorker continued through rocky times supported by cover artist Constantin Alajalov (1900-1987) and cartoonist Peter Arno.

World War II

During the World War II years, 1942-1946, many illustrators like other Americans focused on patriotism and support of the war. Reflecting the general mood of the country, their drawings and paintings became more restrained and unresponsive to the lavish styles of Harvey Dunn, Harold Sundblom and Maxfield Parrish.

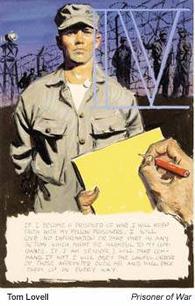

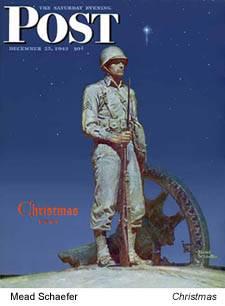

Some illustrators such as cartoonist Gilbert Bundy (1911-1955) and Harold Von Schmidt became artist-war correspondents. Bundy saw combat in the South Pacific and spent 24 hours in water, the sole survivor of an attack. Tom Lovell (1909-1997) was a staff sergeant in the U.S. Marine Corps, and did paintings that remain the most extensive Marine Corps visual history of World War II. Harold Von Schmidt designed posters for the U.S. Navy, served as invited artist-correspondent for the U.S. Air Force in the European theatre, and was artist correspondent for King Features. Al Parker was popular, especially in the Ladies Home Journal, because of his widely published magazine fiction mostly directed to families, especially women, waiting for returning soldiers. Mead Schaeffer (1898-1980) painted many Saturday Evening Post covers showing soldiers in various branches of the service. Under the auspices of the military, his work was exhibited in more than ninety cities in the U.S. and Canada to stir support for the war.

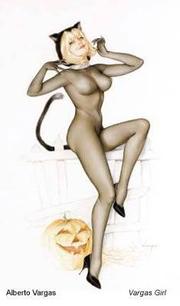

Images of pin-up girls were much sought after by American troops, and illustrators such as Alberto Vargas (1896-1983) met those demands. His ‘girlie’ pictures were reproduced in the millions, which earned him a post-war sixteen-year contract with Playboy magazine. Gil Elvgren (1914-1980), a student of Haddon Sundblom, was referred to as the ‘Norman Rockwell of cheesecake’. Many of Evgren’s damsels found themselves in distressing situations that caused their skirts to fly high.

Zoe Mozert (1904-1993) was unique, not only for her art talent, but for being a female pin-up artist. She began her career during World War II and had a thriving profession after the war. Brown and Bigelow editors hired her for their calendars. She also illustrated for romance magazines such as True Confessions, and was a movie-poster artist including for The Outlaw, starring Jane Russell and Howard Hughes. Howard Christy created ‘The Christy Girl, which for many persons established the American concept of feminine beauty. According to Judith Cutler, co-founder of the National Museum of American Illustration, Christy’s female images set the criteria for contest winners in the Miss America Pageant”, which was begun in the 1920s. (Goldsmith 64) A focus on appealing to women rather than men with pin-ups was the goal of Jon Whitcomb (1906-1988), who did male pin-ups for females waiting for their lovers to return from the War.

The Golden Age

Although Mary Foote was traveling in the West and was quite isolated from illustration activity in the East, she, like many others in her profession, was benefiting from a surge of public interest that culminated with a period retrospectively called ‘The Golden Age of Illustration’. This ‘golden’ time was a period when illustrators were recipients of the benefits of a huge post-Civil War economic and global market expansion. A lively American economy and culture stimulated a demand for grandiose visual materials including posters and other advertisements. Carrying into the 20th century, this activity generated ever-increasing public interest, which in turn was fed by a proliferation of magazines, newspapers and novels. It was a country ‘on-the-move’, and for illustrators that energy translated to a ‘golden era’, remunerative financially and psychologically. Walt Reed wrote that it was an “era when all of the elements that engendered illustration’s ‘Golden Age’ came together.” (87)

In lockstep were technological advances with increasingly sophisticated printing equipment, low prices for paper and halftone processes that made quality copies of artists’ work by sidestepping engravings. The really big ‘door’ opened in 1881 when “American photographer and inventor Frederick Eugene Ives patented the halftone, which made it possible to reproduce the illustrator’s work with remarkable fidelity.” (American Art Quarterly, p. 40) Initially halftones were limited to black and white and were not of the best quality, but were revolutionary because the “middle-person”, the engraver, was made obsolete. The second big advancement was in the late 1880s when the invention of a four-color method facilitated color reproductions in large quantities. For book and magazine illustrators, this innovation meant that palettes, brushes, easels and canvases could be tools as well as the traditional approaches with pen, ink, pencils and paper. Armed with new methods such as color and brushes and insurance that the image created was the one that would be printed, illustrators could become much more experimental and imaginative. For some art professionals, it was the closing of the divide between illustrators and fine-art painters.

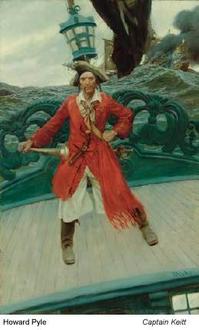

Much of what happened during this ‘Golden Age’ is linked to Howard Pyle (1853-1911), the “Father of American Illustration” (Falk 2680). Pyle began his teaching career when illustrators were in high demand because newspapers and periodicals were chief sources of information. However, production pressure combined with ill-trained artists was responsible for increasingly slip-shod work.

Pyle, however, stood out from many of his peers not only for his skill but for the ensuing international attention that made him a celebrity among American illustrators. By the 1880s, he was receiving rave reviews from European as well as American writers for his pen and ink magazine and book illustrations including The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, published in 1883. Indicative of the praise he was attracting are words written from Europe September 11, 1882 by Dutch artist Vincent Van Gogh in a letter to his brother Theo: “Do you know an American magazine called Harper’s Monthly? There are things in it, which strike me dumb with admiration, including . . . sketches of a Quaker town in the olden days by Howard Pyle. I am full of new pleasure in those things, because I have hope of making things that have soul in them myself.” (Carter, Beaux 45)

Van Gogh was responding to a quality of Pyle’s work that set his work apart from common frozen-seeming images illustrators were creating to support written text. Combining historical accuracy with ‘in-your-face’ action images, Howard Pyle grabbed attention because his illustrations stirred passion, excitement and mystery, and were so aggressive that viewers were denied safety zones for retreat.

Howard Pyle’s teaching was innovative for several reasons. He was committed to a rigorous course of education for illustrators because of his great respect for the profession. He taught that the focus should be on American subjects, both historical and current; and that illustration images should be aggressive and demanding of the viewer’s attention.

Pyle’s teaching career began in 1894 at the Drexel School of Art in Philadelphia and continued with the Pyle School of Art from 1900 to 1906. In 1903, he also established a school on the Brandywine River near the border between Delaware and Pennsylvania, and ‘Brandywine School’ became the collective name for Pyle’s students and their subsequent early 20th-century domination of American illustration. He also conducted summer-school classes at Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, building on the reputation and philosophies of Felix Octavius Carr Darley who had moved from New York City to the area in 1859.

Before starting at Drexel, Pyle had applied to teach at the Pennsylvania Academy but was turned down because his subject was ‘applied’ art rather than purely aesthetic. It was a slight he never forgot. Some years later, when the Academy sought him out to teach classes, he found satisfaction in turning down the offer.

Described as unselfish and encouraging of his students, Pyle was also unique because of his encouragement to women in an era when their filling “breadwinning” illustration jobs was not considered ‘ladylike’. Pyle, however, encouraged women to enroll in his classes, but he did qualify his actions by saying that when a woman married “that was the end of her” professionally. He also expressed great frustration about the behavior of some female students. Shouting to a friend, he said: “I can’t stand those damned women in the front row who placidly knit while I try to strike sparks from an imagination they don’t have.” (Carter, Red Rose Girls, 44)

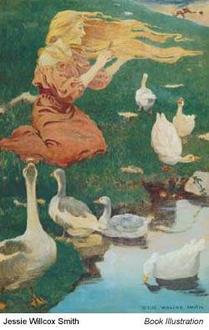

Over forty women became students of Pyle including ones whose names remain prominent as American illustrators: Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935), Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871-1954), Ethel Franklin Betts (1878-), Violet Oakley (1874-1961), Anna Whelan Betts (1873-1959), Charlotte Harding (1873-1951); Alice Barber Stephens (1858-1932), Gertrude Kay (1884-1939), and Sarah Stilwell Weber (1878-1939) and Pyle’s sister, Katharine Pyle (1863-1938).

Other big-name illustrators among Pyle’s students are Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966); Harvey Dunn; Stanley Massey Arthurs (1877-1950); Frank Schoonover (1877-1972); N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945) and Dean Cornwell (1892-1960). Schoonover was a special favorite and remained a close friend.

Of this era, Edward Penfield (1866-1925) was a leading poster artist. People demanded news on the spot, which led to sketch artists depicting unfolding news. William Randolph Hearst, newspaper magnate, hired Frederic Remington for on-the spot reporting of the Spanish-American War in 1898. Howard Chandler Christy (1873-1952), known especially for his sumptuous nudes, first made his reputation during the Spanish American War when he accompanied American troops to Cuba. He was on assignment from Scribner’s and Leslie’s Weekly.

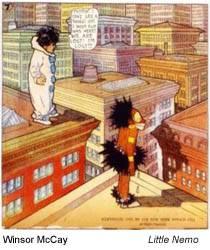

Charles Reinhart (1844-1896) who had died at the end of the previous decade was a transition illustrator into the ‘Golden Age’, which included the above mentioned Maxfield Parrish, Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth as well as Edwin Austin Abbey (1852-1911), James Montgomery Flagg (1877-1960), Charles Russell, Winsor McCay (1869-1934), Frank Schoonover, Jessie Willcox Smith, Francis Luis Mora, (1874-1940) Robert Blum (1857-1903), Walt Kuhn (1877-1949), Everett Shinn (1876-1953), Florence Scovel Shinn (1869-1940), John Sloan (1871-1951), and Arthur Burdett Frost (1851-1928).

Harper’s Weekly, Scribner’s Magazine, McClure’s Magazine and The Century Magazine continued to thrive, having been well established. Other ‘players’ entered the magazine market including The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s Weekly, Woman’s Home Companion, McCall’s, American Magazine and special focus publications such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar for fashion and Outing for outdoor activities.

At the same time, some highly commissioned illustrators became wealthy. Jessie Willcox Smith was dubbed ‘The Mint’ because of her financial success with children’s books. With their big earnings, the Leyendecker brothers, Frank (1878-1924) and Joseph (1874-1951), built a show-place chateau in New Rochelle. They had done well with a secret recipe combining oil and turpentine, and had also perfected a cross-hatch, oil-paint method that gave the speed of pencil and the visual impact of color without the brush going dry. These innovations allowed the brothers to work more quickly than their peers.

After the Golden Era

Economic hard times in the 1920s and 1930s brought all thoughts of ‘golden ages’ to an end in the public mind. Increasingly illustrators and other artists depicted poignant scenes of suffering and poverty as well as orgiastic behavior by those determined not to succumb to dark reality. Some illustrators became key players in the art movement of Social Realism whose leader was painter and teacher Robert Henri and whose message was revolutionary. He told his students: “To have art in America will not be to sit like a pack rat on a pile of collected art of the past. . . If you want to be an historical painter, let your history be of your own time, of what you can get to know personally.” (Henri, 132, 218) He was committed to American art reflecting American life—the pretty, the ugly and in-between. It was not always a pretty picture, and many illustrators took the message very seriously including friends of Henri’s who had met him in Philadelphia when he was teaching at the Pennyslvania Academy, 1886-1888, and they were artist-reporters for The Philadelphia Press: John Sloan, George Luks (1867-1933) Everett Shinn, and William Glackens (1870-1938). The alliance then continued in New York City where they all settled in the early 1900s and found much of their subject matter on the streets of that big city.

Illustrator Reginald Marsh (1898-1954), a student of Sloan and Luks at the Art Students League, supported himself in the 1920s with urban-realist genre scenes of Depression-era New Yorkers, many of them young shop girls or show girls ‘desperately’ trying to have fun and earn money. The New Yorker Magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, and the Daily News published his work, and in contrast to his subjects, Marsh was from a well-established family, and had more economic security than most of his peers.

World War I stimulated much patriotic illustration such as posters and billboards, and the Division of Pictorial Publicity, a branch of the Committee of Public Information, assigned projects to artists. Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944) chaired the Division, and eight illustrators including Harvey Dunn and Ernest Peixotto (1869-1940) were sent to the front lines in Europe to record the war. James Montgomery Flagg produced many World War I posters, and George Bellows (1882-1925), a regular contributor to The Century Magazine and Hearst publications, did a series of World War I lithographs of German atrocities including the murder of Edith Cavell, a nurse aiding Allied soldiers.

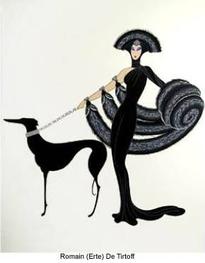

Counter to the hard-core reality images of World War I was fashion-design illustration, which catered especially to ‘feminine’ interests led by Vogue magazine and its most prominent early illustrator Helen Dryden (1887-1981). She worked for the magazine from 1911 to 1923, and, with her drawings of haughty, cosmopolitan Art Nouveau figures, gave the publication its signature look of sleek sophistication. Rene Bouche (1906-1963) began his career as a Vogue illustrator in 1938 with the Paris edition, and his drawing skills were so much in demand that he attracted many big-name advertising clients such as Helena Rubenstein, Elizabeth Arden and Sak’s Fifth Avenue. Romain de Tirtoff (1892-1990), who took the name of Erte, had a twenty-year exclusive contract with Harper’s Bazaar beginning 1915, and replaced the soft Art Nouveau look with Art Deco, characterized by hard-edged linearity.

Following World War I, illustration art reflected people in a restless, quickly-changing society that flaunted traditional values, was increasingly traveling about the country thanks to automobiles, and receptive to mass production and advertising that promoted the new availability of products. Fitting into this mode were quick-read magazines that provided an entertaining, lighthearted combination of visual images and human-interest stories.

Center stage among this type of periodical was The Saturday Evening Post, which had grown into one of the major publications of the 20th century. Founded in 1821 as a four-page newspaper with no illustrations and no controversial topics, by 1855 it was a family newspaper with circulation of 90,000 subscribers. By the end of that century, financial problems brought it down, but it was revived when Cyrus Curtis, owner of the Ladies Home Journal, purchased it for $1000. Dedicated to topics of business, romance, conservative politics and public affairs, and with emphasis on family and morality, the Post was described by writer Upton Sinclair as “standardized as soda crackers”. . . (Spartacus.net)

Apparently that formula worked. By 1913, the Post had a circulation of over 2,000,000, and three years later, 22 year-old Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) joined the staff as a cover artist. It was the beginning of a 45-year relationship, ending in December 1963 with the completion of 317 covers. Six years later the Post ceased publication because printing costs were too high. Editorial cost cutting by omitting the expensive covers killed profitable circulation and made it obvious that people ‘read’ the Post by its covers, and that likely their favorite ‘read’ was Norman Rockwell.

Rockwell’s name became synonymous with The Saturday Evening Post covers depicting humorous and familiar middle-class genre scenes. Because of his vast exposure in most American homes, Norman Rockwell became the name most associated with American illustration in the mid 20th Century. And he is the painting and drawing master whose images stamped in people’s minds that retrospective golden age that many persons have continued to reference—the ‘once was’ when American life was the way it ‘should be’ with happy families and wholesome activity, peppered with affection and good humor.

In the early part of the 20th century, other successful magazines provided income for talented illustrators. Neysa

McMein (1888-1949) painted pastel cover girls for McCall’s magazine. She was part of the Algonquin Round Table group of writers and artists that gathered at the New York Algonquin Hotel in the 1920s. Peter Arno (1904-1968), Rea Irvin (1881-1972), John Held, Jr. (1889-1958), and Constantin Alajalov (1900-1987) provided early cover art for The New Yorker magazine, an ‘about-town’ publication whose editor, Harold Ross, was also a member of the Algonquin group. Rea Irvin, The New Yorker’s first art editor who served for 21 years, created Eustice Tilly, the magazine’s signature image. Tilly was a caricature of a man who thought he was an aristocratic ‘somebody’ but in fact was ‘silly’. Irvin drew him as a super-sophisticated appearing man with nose-in-the-air, and holding a monocle and wearing a top hat. This image was on the first New Yorker cover and appeared for many succeeding years on the anniversary issue. Beginning 1938, Arthur Getz (1913-1996) took over as cover artist for The New Yorker, and by the end of his career had painted more covers for that magazine than any other illustrator.

In Chicago, teacher and artist Haddon Sundblom (1899-1976) dominated the illustration field after World War I for the next forty years. He trained a number of artists who became collectively known as the “Sundblom Circle” including magazine and book illustrator Coby Whitmore (1913-1988) whose realist-impressionist style incorporated richly costumed figures and lavish colors. This presentation was a marked departure from standardized commercial art in that it seemed to be a fine-art easel painting in the tradition of Anders Zorn and John Singer Sargent. Of Whitmore’s career, Walt Reed of Illustration House wrote: “Probably no other illustrator has been so inventive over so long a time in doing variations on the theme of ‘boy meets girl’. (332)

New Deal Art: the WPA and FAP

An acronym for Works Progress Administration, the WPA was a federal program established with a budget of thirty-five million dollars by the U.S. government to provide economic relief to citizens suffering during the Great Depression. Its director was Harry L. Hopkins, an ex social worker who had come from modest means. He argued that writers, artists, musicians, and theater people were out of work as well as laborers and farmers. An additional catalyst for financial support for art was a letter to the President written by artist George Biddle (1885-1973), a friend and former classmate of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, calling for relief for artists. Biddle’s lobbying is considered the seed for all the New Deal art projects. Congress agreed to allocate seven percent of WPA funding to employ those groups.

The Federal Art Project (FAP), which opened in August 1935, was the visual arts division of the New Deal WPA. The basic premise behind the FAP was that there should be ‘art for every man’; since the New Dealers believed that art should be accessible to everyone. Holger Cahill, director of exhibitions at the American Museum of Modern Art (New York City), was selected to be its director. The FAP is one of the numerous ‘alphabet soup’ labels often bundled together and referred to under the general umbrella term of ‘WPA’. Prior to the FAP, Roosevelt had made previous attempts to provide employment for artists on relief, in particular the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP.), which operated from 1933 to 1934, as well as the Treasury Department Section of Painting and Sculpture created in 1934. The Treasury Relief Art Project (TRAP) ran concurrently with the FAP for several years, supporting artists from July 1935 until June 1938. TRAP artists were not on relief or necessarily in financial need. They were awarded commissions based on the results of a competition. The FAP, however, became the most far-reaching program.

The Federal Art Project, which lasted until April 1943, provided employment for approximately five-thousand artists, who created posters, murals, and paintings, and other artworks, some of which are among the most significant works of public art in the country. The goals of the FAP were to employ out of work artists and provide art for tax-supported buildings such as courthouses, post offices, and libraries. Often realistic, historical, and sentimental, these works produced during the Depression era have been called American Renaissance expressions by some, and dismissed as propagandist by others. One notable inspiration for many of these artists was Mexican painter and muralist, Diego Rivera (1886-1957) who spent time in this country and is known for scenes he created on public buildings, depicting American life. Although he was not a WPA artist, the political concerns he addressed in his work, served as inspiration to later WPA artists.

The Federal Art Project existed in the forty-eight states, and its strongest outreach program was in art education for children. FAP maintained more than 100 community art centers across the nation, managed art programs, and held art exhibitions of works produced by children and adults. By 1940 there were over one-hundred federal art centers and federal art galleries throughout the United States. Art classes, exhibits, and lectures provided opportunities for making art more accessible to average Americans. These programs spawned a new awareness of and appreciation for American art, along with providing jobs for needy artists.

To qualify for work in the FAP, artists had to meet certain professional standards, and also the relief requirements of their home state. They were reviewed periodically, and could be removed from a project if their work was unsatisfactory or their financial status changed. Nearly every known artist of the period, except those who had regular teaching jobs, became involved, and well-respected artists headed divisions reflecting their special skills: Burgoyne Diller (1906-1965) for Muralists, Girolamo Piccoli (1902- ) for Sculptors, Ernest Limbach (early 20th c.), and Gustave Von Groschwitz (1906- ) for Graphic Artists and Alexander Stavenitz (1901-1960) for Teachers.

These section heads determined artists’ eligibility from resumes and data showing financial need. Once accepted, artists were allowed to transfer among various divisions, and the most popular areas were easel and mural painting, teaching, and printmaking. They produced over 200,000 works of art including oil paintings, murals, sculptures, watercolors, etchings and drawings. Among the notable artists supported by the project were Jackson Pollock (1912-1956), William Gropper (1897-1977), Willem de Kooning (1904-1997), Leon Bibel (1912-1995) and Ben Shahn (1898-1969) whose work, The Riveter is in the Bronx New York central postal station. About 75% of the FAP artists were concentrated in urban areas, and Roosevelt indicated some disappointment to the project director Cahill for not better reaching rural areas.

The works of the Easel Division emphasized nationalism and the rediscovery of America via art subjects. In the Mural Division, the focus was on artwork for public places, and varying themes resulted from artists working in regions throughout the country, such as social-realist scenes in Chicago, abstract murals in New York, and Oriental themes in California. For the Sculpture Division, artists were encouraged to experiment with less expensive, non-traditional materials such as wood in sculpture as opposed to bronze. Graphic artists were also encouraged to be economical and practical. Many produced ‘promotional’ posters for the government. Prints of the two-dimensional works remain in circulation, and many are highly collectible as are works with the initials ‘WPA’ after the artist’s signature.

When accepted to the project, artists were classified according to skill level, and the amount they received, between $25.00 and $35.00 a week, depended on their assigned skill level. Easel artist participants worked from their own studios and turned in their artwork on a weekly basis. Waiting in line for their paychecks gave many of them a chance to socialize and exchange ideas with each other. The majority of the paintings were oil on canvas or board, and only a few worked with water-based paints. Participants were given freedom of expression, and styles ranged from Social Realism to Surrealism to total Abstraction.